Introduction: What scaling actually means

A note: This is not the kind of guide you’d get from a major tech consultancy. We don’t do fancy slide decks and book-sized process descriptions (unless that’s really-really what you want). The whole point of this is to flip the normal approach on its side, so it can work. Because the fancy approaches … almost … work. Just all too often not quite. On to it.

If you’ve ever worked in operations or engineering for a large manufacturer, you know the pressure:

The executive team has the (sensible) idea to modernize and digitize production. But nobody at your company has ever done that specific program. To build “energy”, the executives set tight deadlines. But in practice, you start to see red flags.

The intent always made sense. Plants often don’t start at full complexity. Instead, more lines come online over time. More equipment requires attention. And more data flows in from scattered systems. Meanwhile, expectations rise for tighter energy use, steadier uptime, and safer operations. It becomes harder to keep track of even the most basic things.

A big initiative feels like the right match for a big problem. New platforms promise standardization, data lakes promise visibility, and cross-functional workstreams promise discipline.

In practice, though, the weight of those structures slows everything down fast. What looks scalable on a slide often turns into gridlock on the floor.

Luckily there is a simpler way, which still gets you to scale, just in a way that delivers value earlier and more often.

A more healthy path to scale often points to solving one problem cleanly, proving the value early enough that people trust the signal, and then expanding those same mechanics across plants. It grows because it works through repetition and fine-tuning, just like everyday production, not because someone mandated it.

This guide lays out how to build that kind of scale, one loop at a time.

Why multi-plant digital initiatives stall

The problems you experience hold true across industries. But they are especially big in manufacturing because every change you make during improvement and digitization efforts is high-stakes (e.g., in terms of cost per each or sheer impact volume on a high-volume line), and because the devices involved can simply get quite pricey.

By contrast, pure-software companies can often meter changes in smaller batches and course-correct without interfering with large-scale, physical hardware.

That means scaling insights across plants is a significant effort by nature. And it comes with inherent problems:

Problem 1: Big-bang programs break before they help

Big programs often start with equally big expectations. Multiple workstreams spin up with “rigorous” (but heavy) governance. Central data teams draft system diagrams that look elegant and comprehensive. Program managers outline multi-year journeys meant to create visibility across the entire network.

Things slow down soon after the real work starts. Interdependencies stack up. Early decisions require late-stage clarity. Approval asks pile on. Before long, teams wait for value that only arrives after everything is wired together. In many cases, it never does.

This might seem a new problem, given the failed AI pilots lampooned in the media. But it’s been a scourge of digital transformations for years now. For example, almost 10 years ago, McKinsey and the World Economic Forum’s research already found then what sounds just as relevant today:

“Despite … focus and enthusiasm, … many companies are experiencing ‘pilot purgatory’ in which they have significant activity underway, but are not yet seeing meaningful bottom-line benefits from this.”

Basically, many digital manufacturing pilots stall because they never get to the point of delivering early value, though that’s what matters most.

The intention is rigor for scale. But the lived experience is stalling from excessive overhead that the program can’t support.

Problem 2: Teams underestimate effort and the real learning curve

Projects that look tidy in planning turn messy during implementation.

Data structures need more tuning than expected. Operators need time to learn new signals. Maintenance must adjust routines. Supervisors juggle production priorities with new workflows. These frictions are just reality that you should expect, not signs of poor planning. People are doing things for the first time, after all.

Adoption load is one of the major causes of program slowdowns. That’s true both in general and because the tech that factories install need to be so customized and, as a result, have such limited documentation:

“[O]ne of the most significant obstacles that complicate digital technologies’ adoption is the absence of usage standards …. There is no uniform way to identify or use it. This makes the technology be used in different ways and [system integration] complicated …. This challenge increases significantly in the [small and mid-sized companies] that supply large corporations.” (18th International Conference in Manufacturing Research ICMR 2021)

You cannot avoid this early learning load. But you can plan for it.

Problem 3: Teams confuse “buying a tool” with “solving a problem”

A tool creates possibility. It sure feels liberating. But it does not create outcomes. Teams sometimes treat the purchase as progress and then lose momentum once they face the daily work needed to turn insights into actions.

This is not specific to Industry, let alone any sector within it. Here is just a small sample to illustrate the breadth of the issue:

For example, in aircraft safety, engine failure in a Quantas flight came down not just to mechanical issue but also to factors of tools not doing the work on its own like “language used … not effectively communicat[ing] uncertainty of the statistical analysis to those assessing and approving the concession.” Or in non-destructive testing, a key benefit claimed by a tool provider has nothing to do with AI (that’s also part of the solution) but with “prioritizing usability and reducing the risk of human error.” Even MIT research for the U.S. military doesn’t just talk about weapons systems but covers a litany of issues related to making those new tools work for humans:

“… [H]uman supervisory control challenges that could significantly impact operator performance in [ever more network-centric operations include]: Information overload, appropriate levels of automation, adaptive automation, distributed decision-making through team coordination, complexity measures, decision biases, attention allocation, supervisory monitoring of operators, trust and reliability, and accountability. Network-centric operations will bring increases in the number of information sources, volume of information, operational tempo and elevated levels of uncertainty, all which will place higher cognitive demands on operators. Thus it is critical that NCW research focus not only on technological innovations, but also the strengths and limitations of human-automation interaction in a complex system.” (Reviews of Human Factors and Ergonomics)

Problem 4: Pilot graveyards overwhelm entire programs

Many teams have seen a promising pilot that never spread.

Sometimes the pilot succeeds because local experts carried it on their backs or because the site had conditions no other plant shared. When other sites try to copy the approach, they discover missing instructions, mismatched data setups, or different constraints. Momentum stalls.

The Manufacturing Leadership Council (MLC) refers to this as “pilot purgatory,” followed by “scale purgatory,” where pilots succeed but fail to become repeatable. In fact:

“Manufacturers on average start with eight digital pilot projects and 75% of these fail to scale. [And even if pilots succeed,] Manufacturers are increasingly challenged with duplicating success past their inaugural implementations. [S]cale purgatory inhibits companies from rapidly capitalizing on pilots that could deliver transformational outcomes if they were scaled across the production network in a timely manner. [It takes] many manufacturers five to 10 years to capture desired impact at scale.” (MLC)

In short: Repeating Digitalization Success across Plants is just absurdly hard

We could continue describing problems and examples until the metaphorical cows come home.

But the point is probably one you’ve experienced in your own work anyway: It’s one thing to succeed at a single facility. Scaling across sites is another thing entirely.

Let’s switch to solutions instead.

Scaling requires a different approach: something lighter, clearer, and far more repeatable.

Six principles for scaling Digital Solutions without overload

Luckily, some approaches do reduce the effort of cross-plant scaling to a manageable level, and some tools are simpler than others to scale.

Principle 1: Start with one tight data-to-action loop

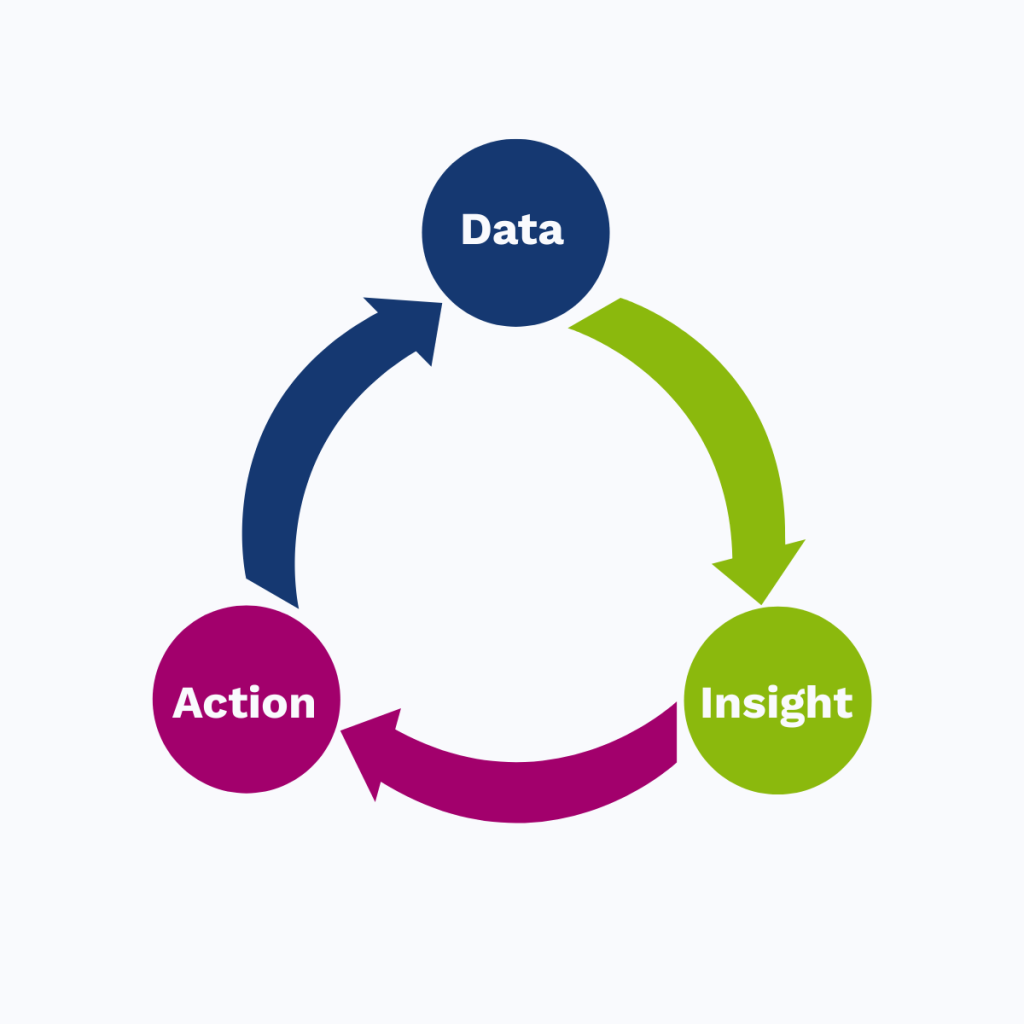

A scalable system begins with one loop that works end to end. Choose a line or an area. Get the data flowing. Turn that data into an insight someone can act on. Then measure the impact. That loop becomes the unit you replicate across sites.

The utter priority in this approach is not to scale until you have realized value. The new tech must be proven in both an operational and business sense.

Some may see that approach as “small thinking.” But it is disciplined thinking. And it makes sense at a gut level. Nothing ever works perfectly the first time round.

The Industrial Internet Consortium explains the reasons for this approach in their guide to digital transformation. And it’s absurdly simple, once you consider it: “The key is to minimize the attendant risks” of the initiative. highlights this

“digitization first [approach.] Unless you are the established technology market leader in your industry, then the most effective strategy is usually that of a ‘fast follower’. The advantages of a fast follower strategy are a combination of reduced risk (only matching competitor initiatives that seem likely to be effective) and speed (taking action quickly, before any initiatives that competitors have undertaken have been able to have a material market share impact).” (IIC)

Your job is to complete Data ➞ Insight ➞ Action loops and resist the temptation to shortcut them. The more and the faster you can complete reliably, the better you get:

Principle 2: Design for effort before impact by involving the “wisdom of your crowds”

Impact is easy to imagine. But effort determines whether you reach it.

Teams often underestimate how much coordination the first deployment requires. A plan that looks simple may still depend on maintenance adjustments, operator training, IT confirmation, and new shift routines. If you do not ask those teams early, the project will discover these frictions under pressure.

While it’s tempting to focus your digitization efforts on “highest impact first” (and that is in fact what some guides recommend), you’ll be better served to get wins under your belt first. Once that’s done, you’ll stand on much firmer ground for dialing up the difficulty for sake of capturing greater impact, e.g., by scaling to plants that run high-risk production.

So far, so obvious. But what companies often miss is that what’s “low-risk” to one team (e.g., engineering) may actually be “high-risk” to another one (e.g., operations). The best way to achieve low risks then is to involve your partner teams early.

If it helps to consider this involvement in the format of a framework, consider the “ARTO” method. It suggests that you must consider four types of factors to achieve low-risk deployment:

- Awareness-related factors

- Readiness-related factors

- Operations-related factors

- Technology selection and readiness-related factors

By checking off all four, you achieve

“holistic and inclusive engagement across all organizational levels, promoting interdepartmental collaboration, customer-centric strategies, and resilience in navigating the complexities of [your digitalization work].” (IEMJ)

Said simply: Don’t just rely on your own judgment for what’s hard or easy. Early engagement reduces rollout risk.

Principle 3: Treat the tool as the smallest part of the work

Tools accelerate action but do not replace it. They need defined owners, updated SOPs, and guidance during the first weeks. And that’s just the obvious part. Incentives, integration with the rest of the org, fending off cultural clashes, and more are just as important but often get overlooked. But consider: Each of your plants has its own culture, priorities, and pride, not to mention headquarters. When one division gets favored or one plant’s solution gets forced on others, people may push back strongly.

Consider the failure of GE’s Predix industrial internet platform in 2018. Even technical challenges aside, the platform failed due to system rejection by the core organization. The change was “so disruptive that the existing organization choke[d] it off.” Billions of dollars in revenue never materialized.

Principle 4: Standardize meaning, not data

A single universal data model rarely works across plants. Equipment, naming conventions, and operator practices differ too much. Building consensus around structure slows teams down when what you need is actionable insight. Entire groups of data scientists can be busy aligning data in beautiful theory before any of it ever affects a single production line.

A better approach is to define shared outcome-based KPIs that matter everywhere. Energy per route. kWh per unit. Simple motor health states. Or something else that matters for your initiative. But focus on the outcomes. Then let each site pursue its own “how,” for example by mapping its local data into those meanings or using their own machines, which inevitably come with their own flavor of data language.

Efforts are underway to create industry-standard data definitions that work for all. But it’s still early days. Just mapping the challenges that industry faces and technologies for solving them in a consistent way is proving difficult.

Meanwhile, you are better off giving your sites some flexibility, rather than forcing a completely standard approach on them.

Principle 5: Use a two-tier operating model

Local teams own fast action because they understand the equipment. Central teams own cross-plant trends because they can see what an individual site cannot. Let each focus on their strength in a balance that uses the best of each.

For example, it may mean that you create value locally as shown above and deploy those “proven-value bundles” in an integrated ways across sites. But at the same time, you may create data and technical infrastructure centrally, with sufficient translation ability for different sites’ reality that you can integrate data and insights consistently, even while you leave sites to implement solutions in their own way.

The key is to focus on interfaces and translations, not to require everyone to do things the same.

Principle 6: Make the second deployment easier than the first

The first deployment proves value. The second proves scalability.

If you are a particularly action-oriented leader, you may push for speed always. No matter what the team proposes, your answer may be “always to do it faster.”

That’s great when everything runs smoothly. But while your team figures things out, it’s worth it to “walk to run.”

In particular, apply the discipline to document every step, capture surprises, and remove site-specific assumptions. Then bring those improvements into the next deployment. After a few cycles, the system becomes easy to repeat.

In the past, such effort would have been tedious. But given modern apps, that excuse is no longer relevant. Modern digital process mapping and adoption platforms make it easy to record digital and even physical work. You absolutely can document what you learn and share the lessons easily.

And that is just one way to make the second install easier than the first. Often, you can get decent results in even simpler ways. For example: Just capture lessons after every meaningful step. Ask “how could this be easier at other plants?” Every competent team can do this. It just takes discipline.

Tata Steel Europe, for example, found during a MES (Manufacturing Execution System) that they struggled to replicate across plants. The company’s consulting arm later described how “[t]emplate-ization and automation helps achieve the timeline goals, cost and quality in limits.” And of course, building templates is only possible if you remember what you actually did.

Pro tip: Anchor everything in a real, must-solve problem

Teams stay committed when the work matters and that can’t be delayed.

If you can ground your digital initiatives in reasons like high-cost lines, recurring downtime issues, or safety concerns, it’ll be easier for teams to keep fighting to make the solution work even when there are challenges. Good leadership helps, as always. But when the problem is clear, good teams don’t even need to await guidance from higher-ups. They can take charge within their own scope to make progress.

This runs directly counter to much of the advice available in social media and thought leader blogs. But it happens to matter anyway:

The common advice is to find “high value” use cases for starting your digital initiatives. But what that advice misses is that high-value work often is under strong scrutiny for uninterrupted production success. New initiatives can’t guarantee that continuity. When something inevitably goes wrong or costs add on, bosses are quick to shelve the previously “strategic” work.

You must engineer situations where the only acceptable path is to persevere and figure out solutions. “Burning the boats” may seem aggressive. And you don’t have to frame it as life and death. But making it clear that the only way forward is for this team to get the tech to perform works wonders for reaching value rather than abandoning work at the first sign of struggles.

Step-by-step guide to scaling insights across plants

Let’s put it all together. How might you best scale digital solutions across multiple plants?

Step 1: Choose the must-solve use case

Pick an issue a plant already feels and can’t handle avoiding any longer. Choose a site with leaders who understand the problem and support the work not to be “innovative” but to solve something that must be dealt with. Overcoming the first challenge and pressing on with a feeling of success under your belt makes a difference.

Step 2: Map the fastest path from data to Value

Make it clear to leadership from the get-go that you will only scale once you have proven value. If anyone challenges that approach as too “slow,” ask them if they feel comfortable spending owner/ shareholder money on unproven speculative solutions.

Step 3: Design A Repeatable, light-weight Implementation Template

Create a plan another site can follow without heroics. Keep track of steps, prerequisites, roles, and early routines throughout. Use digital documentation tech or simple note-keeping to remember it all.

Step 4: Involve stakeholders early and honestly

Start digital initiatives with the “easiest” not “most impactful” use cases. But never believe in your (or bosses’) take on what is “easy” or “hard.” Instead, ask your stakeholders.

Before anything begins, walk the plan through with maintenance, operations, IT, safety, and supervisors. Their feedback will not only save you time later and save you from looking foolish, by helping you avoid simple mistakes. It will also buy you significant goodwill from those other teams, so that, when something goes well, they’ll have your back and make it work.

Step 5: Define your shared “what” and give plants freedom to choose their own “how”

Select a small set of KPIs that matter across plants. Define them tightly and provide example calculations. Consistency will pay off later. But then make it easy for sites to customize their approach to local needs.

For example, if your initiative involves improving your production energy resolution, standard metrics might include:

| KPI | Meaning | Why it scales |

|---|---|---|

| Energy per route | kWh for each production run | Normalizes across different equipment |

| kWh per unit | Product-level energy intensity | Connects energy to margin |

| Motor health R/Y/G | Simple visual health states | Easy for operators to act on |

You can help teams and plants to keep down the effort of dealing with such diferences by providing central resources and teams for converting and integrating local differences rather than either forcing standardization or dealing with messy variation.

Step 6: Set up the two-tier operating model

On a similar note, decide thoughtfully what decisions to let sites make locally and what to centralize.

Beyond decisions, this also extends to doing work once the digital solutions are operational. For example, for predictive maintenance, define who responds to alerts (typically someone local at the plant) and who reviews deeper trends (varies, but often someone at the central level). Clear roles that match everyone’s strengths prevent confusion and make scaling smooth.

Step 7: Launch, learn, refine, and prepare for Plants B, C, and D

Run the first deployment, capture what worked and what didn’t, refine your kit, then move to the next sites. With each cycle, the work gets faster and lighter.

How tools fit in

Tools should make scaling easier, not heavier. The story should never be about “implementing a tool.”

Even early on, while you evaluate tool options, you can already look out for how lightweight and easy to scale tools are.

The best tools install quickly, surface clear insights without major training, and support both plant-level action and central analysis.

For example, look for tools that feature:

- Universal compatibility with all your sites’ machinery and varying brands

- Fast ROI from install to value

- Short learning curves that simplify reaching that value. Especially, look for tools that offer synthesized insights, not raw data that will require a team of data scientists just to make sense of

But even after you find tools that meet all your needs, never forget that the tool is support, not hero:

Must-solve problems give meaning to the work. And your people make the system real, together across teams.

Recap

- Choose tools that speed the path to value and scale

- Prove value via tight data-to-action loops

- Prioritize use cases for effort before impact

- Standardize meaning, not raw data

- Split responsibilities between local action and central learning, to benefit from each of their strengths

- Keep track of your approach, to make the second deployment easier than the first

![[Guide] How to Reduce Machine Downtime: Strategies for SMBs](https://wattwindow.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/ww-how-to-reduce-machine-downtime.webp)

![[Guide] What Is Machine Monitoring, and Why Does It Matter](https://wattwindow.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/ww-what-is-machine-monitoring-and-why-does-it-matter.webp)